Practical Rust - Desktop GUI development with egui (pt. 1)

July 30, 2024 in Development, Practical Rust7 minutes

This is the first in a series of articles that will get your feet wet with desktop application development in Rust.

One of the great challenges in any language when developing a cross-platform application is GUI. Between MacOS, Windows, Gnome, KDE, mobile, and web, it can be difficult to identify a solution that works consistently across the board in all cases. For usability, it’s ideal to work with native GUI frameworks (Win32, Metro, AppKit) as they offer the greatest integration with the host system and generally handle the nuances of working with HID devices. However, at the same time, not every control or concept is equally available across the gamut, and frameworks like Qt or React Native might get you much of the way there. Web-based frontends can also get you most of the way there, but pose their own difficulties and are often not consistent with the host’s general theme.

The solution I’m talking about today, egui (see the web demo here), is a departure from the above options, in that it creates its own from-scratch set of controls and concepts. It is most analogous to (and inspired by) Dear ImGui, the famous C++-based immediate-mode graphical toolkit that promises performance. Rust bindings exist for ImGui, but crossing the Rust <-> C++ language barrier poses assorted challenges and makes for a complicated development stack. egui gives a Rust-native alternative, and with the rapid pace of development that the project enjoys it’s only set to be even better as time moves on.

A quick primer

The first thing to know about egui is that it’s an immediate-mode framework. You render a single frame at a time, and can think of the graphics framework as a pure function that takes state and converts it into that frame. Immediate-mode frameworks are generally very simple compared to the more generally found retained-mode variety, in which portions of the screen are selectively rerendered based on the framework’s internal state and eventing. There are tradeoffs to either approach, and I won’t get too deep into the weeds on this topic, but it’s worth knowing.

In egui’s case, each frame is composed of tessellated shapes, as it’s designed to live in a 3D-rendered environment. The frequent case for something like egui is to offer a graphical toolkit that can live inside a game engine, and as such it is a vector-based output. The code that generates each frame is executed often (ideally fits within a 60-frames-per-second window), and the code is very much in the critical path. For this reason, it’s strongly discouraged to have heavy business logic or state management concerns mixed with render logic, and you might even find yourself managing state with threads if the computation needs get to be too great - getting this wrong can tie up the renderer and box your frame rates, making the application impractical to use.

eframe

Technically, what we’re talking about today is the use of egui specifically for desktop app development, which is most easily accomplished using eframe. In a nutshell, it is an application container framework within which egui lives, and handles system-level concerns like window management, HID events, and communication between the operating system and egui. Looking at its README, you might also notice that it’s not the only option; popular game frameworks like Bevy offer integrations as well.

The fastest way to get from zero to working application is to use the eframe_template repo. Its README offers instructions for using it to provision a barebones application you can build around, which is how this article will proceed; I may offer an alternate article down the road that explains how to integrate it into a pre-existing application, but for now it’s assumed that you have the liberty to fire up a new project.

For this illustration, I’ll simply have you clone the project locally:

$ git clone https://github.com/emilk/eframe_template ./my_first_egui_app

$ cd my_first_egui_app

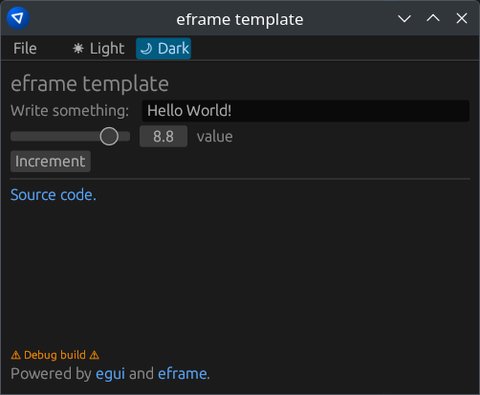

$ cargo runUnless you’re missing any system-level dependencies (see the relevant portion of the README), you should see a simple app pop up on your screen:

Some first steps

I’ll start light today, but wanted to call out a few key features of this application in its out-of-the-box state:

Cargo.toml

Note the [package] section at the top; you likely don’t need to be publishing your own applications under someone else’s

name.

src/main.rs

This is the application’s entry point; in particular, look at the #[cfg(not(target_arch = "wasm32"))] section, as we also have a conditionally compiled

block for WASM output here as well. It is also where the application window gets its title:

eframe::run_native("<title goes here>", ...)Scanning a bit above that, you’ll also notice the NativeOptions section that defines other window characteristics, such

as dimensions and application icon. Feel free to adjust those as necessary to suit your needs.

src/app.rs

This file is where your application lives. It’s defined in the TemplateApp struct, and out of the box has two pieces of state:

label: Stringvalue: f32

There are also some assorted serde-related bits, mostly related to persistent state. Note that if you play with any of the values in the application, close it, and reopen, your state is preserved between runs; this is accomplished with serialization and some persistent storage functionality provided by eframe. This can be opted out of if desired by adjusting the Cargo.toml features to omit the “persistence” toggle.

Also, of particular interest to us, is the impl eframe::App for TemplateApp block; this is where you can customize the assorted

behavioral hooks of the application. Our primary interest is in the ::update(...) function definition, which is called for each

frame to produce the graphical elements we see on the screen. I’d recommend studying the structure of this code to get a feel for how

it results in the output you see on screen; intermixed is some layout-related code (egui::TopBottomPanel, egui::CentralPanel, ui.horizontal(...), etc.)

and the assorted controls (e.g. ui.button("...")).

Regarding the controls, a couple examples give us some good illustrations on how to compose an application’s elements:

ui.horizontal(|ui| {

ui.label("Write something: ");

ui.text_edit_singleline(&mut self.label);

});Here, we have a layouter (horizontal), and inside we present both a text label and a text edit control. The framework is responsible for handling the nuances of updating state, and only requires that you provide it a mutable reference to the String instance you wish to display and update. Similarly, we also have a slider control that takes a mutable reference to the numeric value that backs it.

Also of interest is the “Increment” button:

if ui.button("Increment").clicked() {

self.value += 1.0;

}Here is where the beauty of immediate-mode development comes into play: we simultaneously define both the structure and the behavior of the element (in this case, a button and its relevant click handler) in the same place, and with very procedural-looking code that is easy to reason about. Let’s break it down structurally:

ui.button("Increment")defines the markup and returns aResponsestruct.- That

Responseinstance offers a.clicked()function that indicates whether in the previously rendered frame the button was clicked.

Note the part about the last frame - it’s technically impossible for both the presentation and the event handler logic to coexist in the same frame, as these behaviors are performed in the order encountered. You wouldn’t have an opportunity to click that button before that block executes, since technically this is all a single thread running top-down, so under the hood egui manages input events and tracks when a control has been clicked. Thus, on one frame, a button is clicked, and on the subsequent render you enter the conditional block. In practice, you may notice in certain behaviors (e.g. if you are using the Plotter control and responding to mouse position coordinates) that there is a very subtle lag in UI response to your actions. Generally, though, this is such a tight loop that it’s virtually transparent to end-users.

Some trailing thoughts

I’d highly recommend revisiting that earlier-mentioned web demo to see what all the framework offers; the demo showcases most or all of the important componentry, and should give you a feel for what kind of interface you can compose with this library. I’ll look forward to getting into some more possibilities for UI development in future articles, and hope you’ll stick around to learn more with me.